A few weeks ago I wrote a glowing review of the experiences Marisa and I had while traveling in Taiwan… a jovial celebration of the vulnerability of extended travel, and the wonderful encounters that come out of it. I made a game called “The Kindness of Strangers,” dedicated to all the nice people who helped us along our way. I emerged from Taiwan radiant, optimistic, almost high on the joys of traveling, and the general decency of the human race, excited to continue on and get high all over again in Vietnam.

I suppose I was being naïve. The idea of living life in a perpetual high, whatever brings that high on, is rather ridiculous. Because highs are called “highs” for a reason: if even a small percentage of the population could maintain them indefinitely, they would be called “flats” or simply “life general.” Highs are balanced by lows, and slopes in between. People can’t maintain highs because the world is not of one kind, is not all abundance: a certain drug might make me feel happy, but eventually my supply will run out; I can stuff myself full of food on Thanksgiving Day, but still someone in North Korea will die of starvation; I may encounter ten ridiculously kind strangers in miraculous succession, but turn a corner and I will encounter someone who isn’t so nice. And of course, vice versa. The world is neither white nor black, abundance nor lack, good nor evil, but a mixture of both; in the vocabulary of Asia (and the lens through which Neil Jamieson examines Vietnam’s culture and history in his excellent textbook): yin and yang.

All of this seems ridiculously obvious as I write it, but for me it’s important to remember, because I am prone to extremism, and placing a disproportionate amount of weight in whatever experience I’ve most recently had, or happen to be examining at the moment: this thing that I’m experiencing right now, this is what the world is like. And so my most immediate experience becomes a lens that colors my entire perception of the world, prejudiced greatly over previous experiences I may have had. (Incidentally, I recently finished reading Daniel Gilbert’s rather interesting psychological “detective story,” Stumbling on Happiness, and it appears I’m not alone in this behavior: in general, people seem to be incapable of accurately remembering past experience, and how it made them feel, over the way current experience makes them think that past experience made them feel).

I begin with this perhaps-tedious philosophical drivel, because the encounters Marisa and I have had in Vietnam were by and large so strikingly different from the encounters we had in Taiwan, and I have been trying to make sense of that difference, and also to keep some kind of perspective.

In Taiwan, it seemed that everywhere we went people were simply ridiculously nice to us. So consistently nice to us, that by the time we had been there a couple of weeks we came to expect it, and we let our guards hang low all the time: when the first truck we hailed on the east coast pulled over to hitch us, we didn’t hesitate to throw our bags in the back before we got in ourselves (though we “knew” we should take basic precautions, we just couldn’t bring ourselves to feel cautious at the time, much less suspicious), and when a man in Hualien offered to drive us to the bus station because taxis were rare, we didn’t even think to ask him how much money he wanted (because no one who had helped us had ever wanted any—and he was no exception), never mind thoughts of anything worse.

In Vietnam, by contrast, it seems nearly everyone we’ve met has wanted something of us, and in some cases they’ve been prepared to take it whether the item in question was offered or not. “Friends” have turned out to be mercenaries, and strangers to be swindlers, most of them fairly aggressive. A lot of this “swindling”, mind you, has been unexceptional and—somewhat ironically—simply taken the form of aggressive, unfettered capitalism: guest houses quoting us prices in US Dollars, then insisting on a ludicrous exchange rate if we didn’t settle it ahead of time; taxi drivers setting their meters at the wrong price point because they thought we wouldn’t notice (then getting angry and aggressive when we wanted to disembark); hotel managers selling us $5 bus tickets that actually turned out to be worth 50 cents on packed minibuses full of vomiting children; or, at the start of it all, the government charging us a seemingly arbitrary price for our visas as we entered the country (then shortchanging us when we didn’t have the exact amount they wanted).

On one level, it’s obvious that none of these interactions constitutes “pleasant” by definition; but on another level, it’s hard for me to fully articulate (or defend) why they bother me, when I feel that I should have expected them all. Vietnam is a very poor country, and with ninety million citizens, it ranks thirteenth on the global population scale. The economy, while one of the world’s fastest growing, is still small; per capita GDP sits at a meager $1,100, and prices are low. In this context, next to the average Vietnamese, I am probably not quite a billionaire, but a solid millionaire at least. Why shouldn’t I pay more for a taxi, or a bus ride? Why shouldn’t I give tips out for everything? I’m in a communist country, after all, so why shouldn’t people use their capitalist wile against me for the socialist end of redistributing wealth? Such activity may be inconsistent and unregulated, but it serves the same purpose that a wealth tax does in developed western nations. The idea, in theory, doesn’t bother me.

Nor does the actual monetary loss. Indeed, our net loss in all this swindling amounted to nothing more than a small mound of pocket change (well, maybe a big mound, but still: pocket change). The idea of contributing something to the Vietnamese economy—as someone of relative wealth passing through the country and availing myself of that economy—actually appeals to me. I want to contribute.

What bothers me, I guess, is the way that everything happened: the feeling I was left with after all these encounters. The feeling that I’d been cheated out of money I didn’t even care about by someone I was hoping to have an amicable interaction with. The feeling that people were sometimes taking great pains to hoodwink me, when I would have gladly paid them more had they asked in a nicer way (or at all). But of course, you can’t buy friendship, and anyway I suspect the unfortunate reality behind many of our encounters was the simple fact that most of the people we interacted with needed money more they did friends.

Another fact to take into account is that most of the negative encounters we’ve had in Vietnam have been with people “of the trade”: people in the business of dealing with (and hustling) tourists and travelers on a regular basis. Vietnam has been on the backpacker trail for a long time, and the country is narrow, which makes it difficult to get off the dreaded “beaten path.” There’s still plenty of wonder to be had on that path (I’ll get to that in a minute), but it’s probably not the best place for authentic, endearing encounters with ordinary Vietnamese. In Taiwan we never gave much thought to getting off “the path,” because we never felt like we were on one: the journey felt more like a journey, and less like a scuttle from one carefully prepared tourist trap to the next.

Finally, in the interest of full disclosure as I describe my perceptions, I will say that towards the start of our time here (while we were still in Hanoi, visiting with Marisa’s family), Marisa’s sister’s hotel room was burgled as she slept; and towards the end of our journey, in Ho Chi Minh City, my camera was stolen out of my hand. I relate these incidents only for full disclosure, because I am well aware that my camera being stolen is more reflective of my own silliness (venturing into the chaos of Tet in Saigon with anything of value) than it is of any part of Vietnamese culture or society. There are thieves everywhere, just as there are kind people everywhere, and I know this. But as we travel, we don’t encounter the objective, we don’t encounter what we know, we don’t encounter statistics. We encounter a unique, bizarre, subjective train of events, that color and change us whether we want them to or not, which is my point. I think as travelers it’s important to realize that, important to admit it.

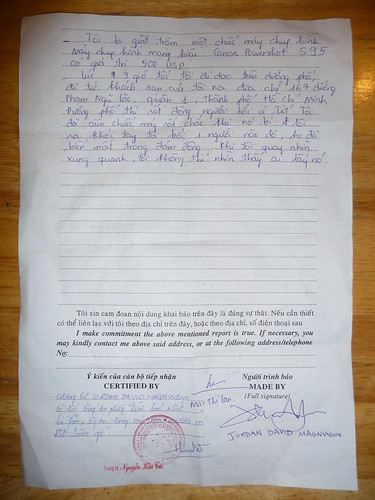

The police report for my camera’s theft… not an easy task to acquire (but necessary for an insurance claim)!

When my camera was stolen out of my hand, in that mass of people, all of whom seemed to be after me (I had physically caught three people going into my pockets before the camera was tugged out of my grip), that moment seemed to me to epitomize my experience in the country. Later, as we waited for a city bus to take us to Saigon’s inter-city terminal, I watched pickpockets hawk their wares to locals, right in front of my eyes (watching hopefully, resentfully for my camera), and I was stunned that no one seemed to care (why should they? A foreign millionaire loses a watch to a poor resident thief… reasonable redistribution, right?). At that moment, that moment seemed to epitomize my experience in the country.

And in some ways it did. But of course in other ways it did not. Despite all these negative encounters I’ve touched on, there were naturally (and happily) moments to balance, moments to bring perspective. Our interactions with people generally did not leave us with the rosy glow that our encounters in Taiwan did, but there were noteworthy exceptions. For example, towards the end of our trip, in the Mekong Delta, a young man we met online offered to take us for lunch with his girlfriend. He was on leave from university in Saigon (for Tet), and was insatiably curious about our travels. We had a wonderful interaction over some delicious street food, and at the end of our meal he presented us with a hand drawn portrait of Marisa and I he had sketched from our photos online (and he didn’t want money for it!).

Later, in Can Tho, another university student offered to host us for two nights in her tiny shack of an apartment where she lived with her sister… her “beautiful apartment” she called it, and it was. She insisted on giving us her bed, and smiled like our intrusion was the best thing that ever happened to her. We went out for smoothies with one of her university friends (who was translating Hawking in his spare time “for fun”), and the discussion we had with them while sipping down delicious fresh fruit was one of the highlights of our entire trip. These bright, friendly, optimistic individuals were an amazing contrast to the people who’d recently been ripping us off, and talking with them (about everything from anthropology to astrophysics to politics to American Idol to Facebook and censorship) helped bring needed perspective to our journey.

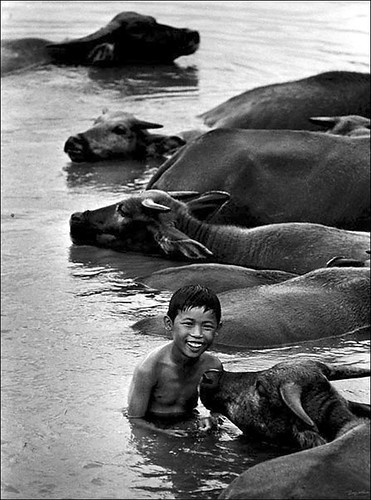

Or there was our encounter with Long Thanh: Vietnam’s most celebrated photographer. While in Nha Trang we went looking for his studio, as Marisa and I are both rather keen on photography; we were especially curious to see some of Mr. Long’s more famous works that we’d heard about, like his photo of a rural Vietnamese boy running across the backs of several submerged water buffalo, which (like many of his pictures) has won him a number of international awards. When we arrived, the studio seemed to be closed (it was Tet-eve, after all), but when we knocked, a young woman opened the door. We took our shoes off and went inside, appreciative of the cool air and quiet surroundings. The space consisted of three consecutive wooden-paneled rooms, lined top-to-bottom with black and white photographs. Long Thanh has been in the business of picture taking for over fifty years, but he has only ever had one subject: Vietnam, and he has only ever envisioned her in black and white. The large print photos were stunning.

Photo copyright Long Thanh.

Still, the real joy of the visit came later on when an older man entered the studio, and began talking with the young woman we had already met, as she showed him something on the hefty digital camera she held in her hands. After a moment, the man took the camera and held it up for us to see a photo of two sleeping cyclo drivers on its rear display: “my daughter took this picture just this afternoon,” he beamed. To make a long story short, the man turned out to be Long Thanh himself, and the woman his daughter. They wanted to keep the gallery open over Tet, so Long’s family was coming to him (his home, he explained, was just upstairs from where we stood). Over the next twenty minutes Mr. Long offered us interesting anecdotes about several of his photos, and before we left we made sure to ask for his best advice for budding amateurs like ourselves; his answer was hardly surprising: he told us to keep our eyes open.

Or there were the chats Marisa and I had over breakfast with a Vietnam War veteran who was staying at our hotel in Saigon; a Michigander who had fathered two Amerasian girls during the war. He told us how he had come back twenty years after the fighting to find them; how he had been wrenched with guilt when he discovered that the older of the two had been murdered, but how he found the other and was reunited happily with her. Now he has a house in Dalat, and was only in Saigon to settle some paperwork before being married to his Vietnamese fiancé.

Besides these happy interactions, there were Vietnam’s natural and historic wonders to inspire us, and those moments of being in a place and feeling amazed to be there, to be traveling, to be alive:

Flying through the countryside in the early morning in Ninh Binh on the back of a moped, watching rice farm after rice farm wiz by, then bam: a giant vertical karst emerging from the center of one of those rice fields. Then another. And another.

Whipping around one of those rocky monoliths and catching site of mammoth Bai Dinh Temple, in the process of being built… soon to be the largest Budhist complex in Vietnam.

Walking around Hue’s Citadel in the light morning rain, no one else there; the flowers and the moss on fire from the rain, burning green instead of yellow or orange; tiles glistening and shimmering; old moats threatening to overflow… a perfect morning to get lost in a fascinating old structure that’s been to hell and back.

Days on the train, feeling connected to generations of travelers who have gone before, who have sat and looked out the window and listened to the clak-a-ty-clak of iron horse wheels as one place turns into another.

Related slideshow: Vietnam Top 10 Train and Bus Shots

Taking the night bus from Hue to Nha Trang. A miserable experience, but an experience nonetheless. Travel doesn’t feel right to me unless there’s some discomfort involved at least some of the time.

Arriving tired and sore in Nha Trang at 5:00am, but feeling joyful as I watched the sun rise over the beach as locals exercised, before catching a few more zzz’s and diving into the five-foot waves.

Finally, I can say that some of the swindling we were subjected to actually lead to a few of our most memorable and interesting experiences. For example, I complained about being sold $5 “tourist bus” tickets for 50 cent “anything but” bus rides earlier, but again, my main grievance was with the way such transactions happened; taking packed local transportation, while not the height of comfort, is an experience I’m happy to have, and the local Vietnamese minibuses are amazing in the way they operate: they have advertised destinations, but will take anyone any part of the way between their two endpoints. People don’t wait for the bus: rather, each one has a worker who hangs out the door, calling out to everyone who passes, and metaphorically and literally pulls people into the fun (and not just people, but goods as well: one bus we were on picked up a large delivery of strong-smelling mushrooms). The main rule of thumb on these busses is that there is no such thing as “too full.” I wasn’t lying about the vomiting children either: one young tyke very narrowly missed a headshot opportunity that would have made the experience even more memorable than it already was.

And this, probably, is as good a place to end as any. Vietnam has offered us mixed experiences, but even those experiences that weren’t particularly comfortable or fun have still been experiences. Travel isn’t about the good things, or the bad things: it’s about all the things that happen to you while you’re in another place. It’s about trying to make sense of what you can, but ultimately, I think, about simply accepting the sum total, which will inevitably be more than can be analyzed or synthesized (and analysis and synthesis, valuable as they are, are not equal to and cannot replace the raw experience itself).

I started this post by reflecting on the negative interactions we’ve had here, not because I feel a lasting dislike for Vietnam, and want to vent some kind of revenge, nor because I think such interactions represent this country in any kind of holistic or objective way. Rather, I started the post the way I did because I am writing about the subjective experience of travel, and as we leave Vietnam the difference between the way we were treated on average here, to the way we were treated in Taiwan—and the effect that difference had on us—is too striking a part of our personal journey to overlook.

It is not about “Taiwan vs. Vietnam,” but about our particular experience in visiting Taiwan, and then Vietnam: because it’s impossible to travel without context, without a “before,” and an “after.” It’s about the fact that I left Taiwan rosy and optimistic, carefree and trusting, and that—despite the good times I’ve recounted—I am leaving Vietnam feeling somewhat cautious, suspicious, and cynical, with an eye to protect what is mine. This change in me is what I think about as I leave this place, and I ask myself, why? Why was our experience so different here? Was it the poverty? Was it the tourist trade? Was it our lack of effort in getting off the beaten path? Was it our unreasonable optimism and naivety brought on by the ridiculously positive experience we had in Taiwan? Was it the distorting lens of significant negative events, like having my camera stolen? Were we just unlucky? Was it all in our heads?

I suspect a bit of all of the above. Whatever the answer, our experience is what it is, and I don’t regret it. Sometimes travel makes me feel like I’m living on a cloud, sometimes it brings me back down to earth. Such is life. Such is the world. And that’s what I’m traveling to encounter. Whether inevitable or not, our experience in Vietnam was in many ways simply a balance to our experience in Taiwan, and I believe that balance is almost always good: yin and yang. What will Cambodia be like?

Related slideshows:

Related resources:

I lived there for almost

I lived there for almost three years, and only witnessed the kind of trouble you mention in the first couple of weeks (besides one stolen phone.) I think you quickly acquire a sixth sense about how to avoid that sort of thing. As you say, any stress is usually over just a few dollars anyway.

I’m sorry your experiences were fairly negative, because I find the Vietnamese to be the some of the warmest and happy people I’ve encountered in my years of travelling. I’ll never forget my time there.

Thanks for the comment

Thanks for the comment Jasper! I appreciate your perspective, and it's awesome to hear the voice of someone who's lived in Vietnam. I hope my post doesn't come off as too negative. I love traveling, and I love a chance to visit any new country. I was excited to visit Vietnam, and as I leave, I'm still glad I got the chance. I hope my post hasn't left the impression that I regret the visit, or that it was all a bad time. As I was writing it, I was tempted, in fact, to leave out the negative details: to focus only on the positive experiences we had in the country. Writing anything negative makes me nervous that people will get the wrong impression of a place, or the wrong impression of me… nervous that I will discourage people from traveling, when I think that traveling is always worth doing; or discourage them from visiting a particular place, when I think that every places has positive and negative characteristics, that no two peoples' experience is ever exactly the same, and that I think every place is worth going to.

I believe that travel is a very personal and subjective thing, though; I think everyone has different experiences in different places… everyone has highs and lows… everyone has more pleasant and more trying encounters. So ultimately, as much as part of me wanted to focus on only the positive parts of our time in Vietnam, I thought it would be dishonest do so.

I hope that it's clear that I don't believe our particular experience reflects objectively on Vietnam as a country, and that I am certain there are millions and millions of wonderful people there (some of whom we did run into)! Thanks again for your post, because it helps to bring that fact home :) .

Not at all, I didn't read it

Not at all, I didn’t read it like that. Just always a shame when your memories are coloured by bad experiences, as some people tend to form their views based on such things - but you also mention many of the things I love about the country (street food, the curiosity that arises from living in a relative bubble, Long Thanh’s photography etc!) One thing I found unique was the relative lack of negativity, conflict and anger in a country that was ravaged for so long by war (1000’s of years if you include Chinese wars.) That in itself is an incredible feat (and reminds me of the peacefulness of the people of Hiroshima.)

If I’d known you were there I’d have pointed out a few killer spots to eat…

Anyway, look forward to the game you create based on this experience!

Cheers,

Jasper

"This is an experience I

“This is an experience I refuse to be denied!”

I love your attitude, Jordan, your balanced perspective. I love the fact that you talk about both the hard things, and your feelings about them, and the good things. This is what it’s about, when it comes to a positive, adaptive experience of another culture (what Bennett calls “ethnorelativism”) vs. a closed, self-centered perspective on and experience of the world (“ethnocentrism”). I would use this piece as a great example of ethnorelative perspective on experience in another culture. It is too easy not to keep the negative experiences in perspective…

Keep writing - I love your reflections. You are a wonderful anthropologist (I take pride in that)!

Great reflection, Jordan.

Great reflection, Jordan. And I love the pictures (and what an awesome sketch!).

I would use this piece as a

I would use this piece as a great example of ethnorelative perspective on experience in another culture. It is too easy not to keep the negative experiences in perspective.

Post new comment