cambodia

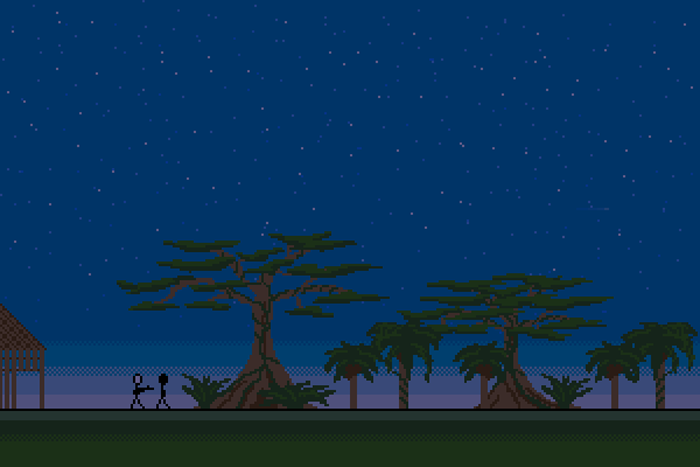

A small sketch about the history of Cambodia. Takes a few minutes to play through, and requires no gaming skills.

The Killer is a new notgame inspired by my experiences traveling through and learning about Cambodia. It can be played from start to finish in about four minutes by anyone, as it requires no gaming skills whatsoever.

Click here to play The Killer now in your browser.

Thanks to all my backers who helped me test and refine this notgame!

Another interactive travel map, courtesy of Marisa:

“Cambodia is like Australia.”

I had been sitting on a boat in the sun all day, coming up the Mekong from Vietnam, and all those rays were making my senses feel a little bit baked. I couldn’t be quite sure if the words I thought I heard came from inside or outside my head.

“Come again?”

“Cambodia is like Australia,” Rob repeated. “People are super laid back here, and friendly. They work hard—really hard—but they know how to kick back and relax hard too, at the end of the day. I love it.”

Rob, an Aussie himself, has been living in Phnom Penh for the last several months, where he unexpectedly set up house after cycling his way up from Singapore on a recumbent tricycle and deciding not to leave. We connected through CouchSurfing.org, and he generously offered to host Marisa and I while in Cambodia’s capital… which is how I came to be sitting on his couch nibbling sweet mango while he compared the Southeast Asian nation I had just crossed into with his homeland down under.

I’ll admit that the comparison caught me by surprise. I didn’t know much about Cambodia before visiting, but the little I knew about the Khmer Rouge regime dominated my mental image: I pictured a country under a dark cloud, devastated and depressed, struggling to recover from untold horrors. Australia, on the other hand exists in my mind as a rather more happy and sunny place.

I still haven’t been to Australia, but after four weeks in Cambodia I can say that the people we’ve encountered here have indeed been incredibly laid back and friendly. People seem to smile with their whole faces on a more regular basis than I remember them doing elsewhere, and this, along with the constant performing of sampeah (bowing with palms together) creates a disarming effect. The sampeah came naturally to me (probably because of all the bowing I did while in Korea), and I caught my smile getting constantly broader under the barrage of friendliness. Soon I found myself entering into easy conversation with all kinds of people: with a woman selling cane juice by the side of the path on a rural farming island outside of Kompong Cham, who taught me several words of Khmer through signs; with a shop vendor who turned out to also be a high school teacher studying English when and where he could—we had a forty-five minute dialogue about our two countries and exchanged emails at the end of it; with Sa Vorn, our tuk-tuk driver in Angkor—a hard-working man who exudes honesty and trustworthiness… and with many others. One highlight was dining with Rob along with his Cambodian fiancée’s family, his future brother-in-law chatting away with us vigorously in pigeon English, alternating questions, jokes, laughter, and directives to “eat more frog legs!” faster than we could keep up (the frog legs, fried with lemon grass and chili, were delicious).

Dinner with Rob and his bride-to-be (before other family members showed up).

So what of the dark cloud? What of the Khmer Rouge? As I learned more about the regime I was shocked to discover that the horror was—if anything—worse than I had previously imagined. In the four years that “Red Khmer” controlled Cambodia, over two million people died from starvation, torture, and brutal killings—a full quarter of the country’s population at that time—making the period deadlier on a per capita, per nation basis than the American Civil War or the Rwandan Genocide.

An image painted by one of the few S-21 prison survivors.

Pol Pot’s communist “revolution” was the most radical ever attempted, making the Soviet and Chinese programs look sensitive and gradual by comparison: in 1975 all foreign ambassadors were evicted, schools and hospitals were closed, banking, currency, and private property were abolished, and religion, romance, and family loyalty were outlawed in one fell swoop without any kind of gradation schedule. Cities were turned into ghost towns as residents were driven into the countryside to perform fieldwork, where they were expected to produce incredible rice yields on meager rations (though many of them were lacking the most basic agrarian knowledge). Power was placed in the hands of the “pure” peasants and children, who were taught to obey all orders and use force indiscriminately, while former city dwellers and “educated elite” were considered corrupted beyond redemption, and thus expendable (excepting party leaders like Pol Pot, who were generally the best-educated of all).

One boy who was arrested then tortured and killed at S-21.

This was the high point of the regime. As the city dwellers failed to produce great quantities of rice, everything got worse. Rations were decreased below starvation level while work hours were prolonged, and violence escalated. Pol Pot, unable to believe that his revolution could fail, suspected corruption within the party. Cadres and lieutenants were arrested and sent to Security Prison 21, where they were tortured until they confessed to working for the KGB, CIA, or Vietnamese government. Then they were asked to name fifty more conspirators (who were predictably brought in next) before they were taken to the killing fields. Their wives and children, charged “guilty by blood,” were also killed (the children usually by beating their heads against trees). These killings were mostly carried out by "pure," barely adolescent teenagers. In the countryside the educated were asked to step forward for “forgiveness,” then beaten to death, while everyone everywhere starved. If the Khmer Rouge had not antagonized Vietnam to the point that the Vietnamese army invaded in 1979 to topple the regime, it is likely that the Cambodian population would have been totally exterminated within a matter of two or three more years, Pol Pot left alone in his utopia, atop a monstrous pile of skulls.

Skulls of victims at the Choeung Ek killing fields.

This is what the kind, smiling, laid back people here have been through. Since the deadly regime was toppled things have been infinitely better in the sense that people aren’t dying by the thousands, but in many ways Cambodia is still in the early stages of recovery. It took decades to rid the country of the last Khmer Rouge insurgents (whom the American government supported gainst the Vietnamese into the 1980s, and who were active into the mid-90s), and the country is still littered with millions of land mines laid to keep those insurgents at bay. Despite a UN attempt to promote fair elections in 1993 the current government remains an offshoot of the one installed by the Vietnamese in 1979, rather than the people’s choice, and is largely irresponsible and unresponsive, making little attempt to meet its nation’s basic health and education needs, relying instead on foreign aid (much of which seems to vanish as it enters the country). Corruption is rampant and widespread (with Transparency International ranking the country in the bottom 1% in their worldwide corruption index). Many former Khmer Rouge leaders and cadres are in powerful positions in the current government, and many more live ordinary civilian lives, having never been asked to account for past deeds. In 2006 an international tribunal was established to try the most senior KR leaders, but it has met with numerous bumps in the road, and only one person has been convicted to date, with their sentence now being appealed.

After the bows and the smiles and the gracious hospitality, these realities did come out in my discussions with Cambodians. In hushed tones people asked me if I had visited Choeung Ek, then explained how they were attempting to process the horrors of their country’s past. “How could this happen?” They asked me. “And why?”

As if I could provide any answers.

“This past is not taught in our schools,” said Sa Vorn gravely, before going on to tell me of Cambodia's widespread corruption and how it affected his job, along with other grievances he had with the government. Then he smiled, picked up the English grammar book that he spends all his spare time studying, started up his tuk-tuk, and drove us on to the Bayon… one of Angkor’s largest and most impressive temples, built by Cambodia’s most beloved King at the height of their empire’s splendor. The sun was just rising, and there was not another soul in sight.

Sa Vorn, studying his English while he waits for us at a temple stop—no kidding, that's a grammar book.

And this has been my experience of Cambodia. Learning about one of the worst autogenocides in human history while interacting with some of the nicest, most laid back people I’ve ever met, in the shadow of a staggeringly majestic bygone era. I don't know if Cambodia is like Australia, but it certainly isn't like any place I've ever been.

This, again, is why I travel.

The Bayon at sunrise.

Related slideshows:

Bonus! A few interesting facts about Cambodia:

- Buddhism is the professed faith of 95% of Cambodia's population, which is the highest percentage of Buddhist believers in the world (tied with Thailand). All Cambodian men over the age of sixteen are expected to serve some time as monks as a kind of right of passage.

- Cambodia's chief cultural influence is India, rather than China.

- Unlike neighboring languages like Thai, Lao, and Vietnamese, Khmer is a non-tonal language.

- While Cambodia has its own currency (the Cambodian riel), its use is limited mainly to pocket change, with the country's main legal tender being the US dollar (which all ATMs dispense—at amounts up to $2000 per go!). Generally you pay for things in dollars, and get any change less than $1.00 back in riel.

- Cambodia is the cheapest place in the world to buy certain electronics, notably Apple products, high-end cameras, and other items with relatively determined retail values. Prices are typically equal to their counterparts in the United States (where electronics are still cheaper than most "hyped" locations in Asia due to market differences), but have the advantage of being completely untaxed to everyone.

- Cambodians like their beer with lots of ice. Which of course makes sense for a country with Cambodia's climate.