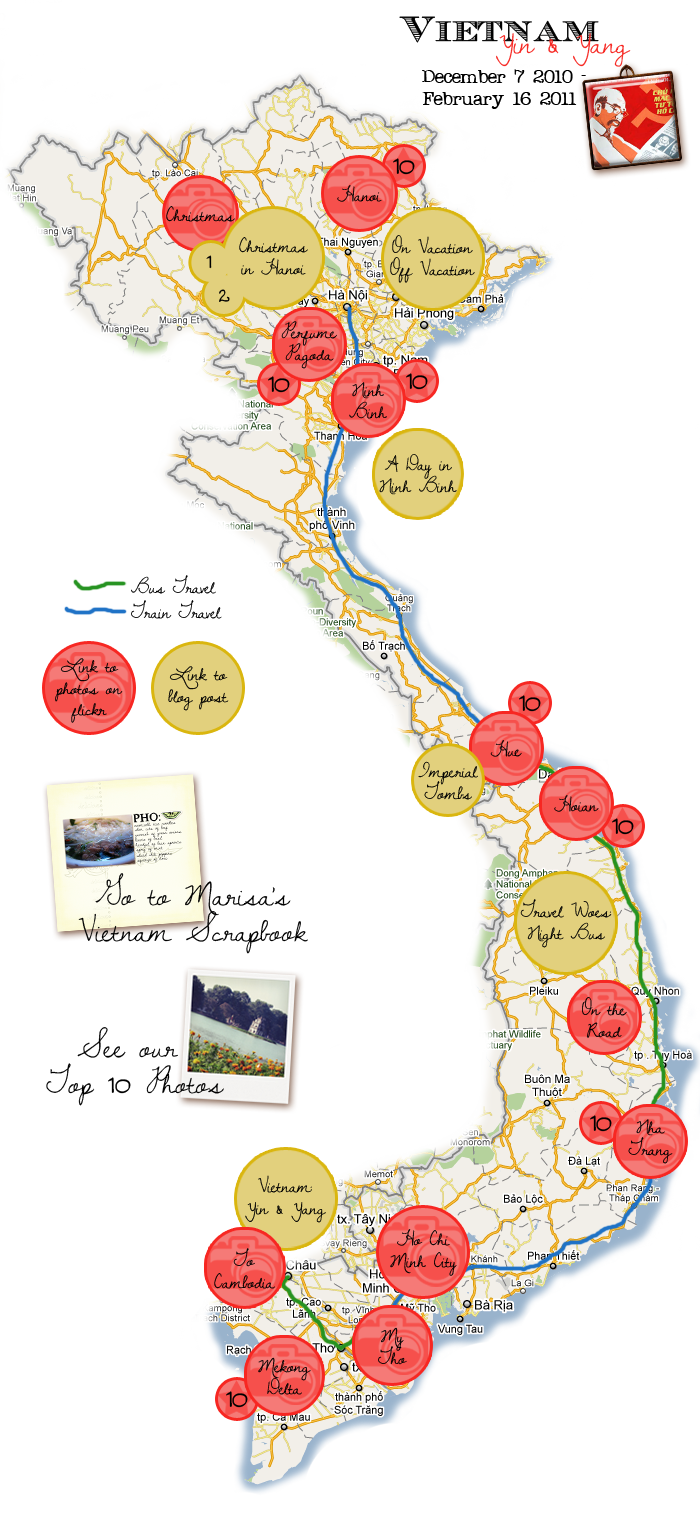

Another interactive travel map, courtesy of Marisa:

“Cambodia is like Australia.”

I had been sitting on a boat in the sun all day, coming up the Mekong from Vietnam, and all those rays were making my senses feel a little bit baked. I couldn’t be quite sure if the words I thought I heard came from inside or outside my head.

“Come again?”

“Cambodia is like Australia,” Rob repeated. “People are super laid back here, and friendly. They work hard—really hard—but they know how to kick back and relax hard too, at the end of the day. I love it.”

Rob, an Aussie himself, has been living in Phnom Penh for the last several months, where he unexpectedly set up house after cycling his way up from Singapore on a recumbent tricycle and deciding not to leave. We connected through CouchSurfing.org, and he generously offered to host Marisa and I while in Cambodia’s capital… which is how I came to be sitting on his couch nibbling sweet mango while he compared the Southeast Asian nation I had just crossed into with his homeland down under.

I’ll admit that the comparison caught me by surprise. I didn’t know much about Cambodia before visiting, but the little I knew about the Khmer Rouge regime dominated my mental image: I pictured a country under a dark cloud, devastated and depressed, struggling to recover from untold horrors. Australia, on the other hand exists in my mind as a rather more happy and sunny place.

I still haven’t been to Australia, but after four weeks in Cambodia I can say that the people we’ve encountered here have indeed been incredibly laid back and friendly. People seem to smile with their whole faces on a more regular basis than I remember them doing elsewhere, and this, along with the constant performing of sampeah (bowing with palms together) creates a disarming effect. The sampeah came naturally to me (probably because of all the bowing I did while in Korea), and I caught my smile getting constantly broader under the barrage of friendliness. Soon I found myself entering into easy conversation with all kinds of people: with a woman selling cane juice by the side of the path on a rural farming island outside of Kompong Cham, who taught me several words of Khmer through signs; with a shop vendor who turned out to also be a high school teacher studying English when and where he could—we had a forty-five minute dialogue about our two countries and exchanged emails at the end of it; with Sa Vorn, our tuk-tuk driver in Angkor—a hard-working man who exudes honesty and trustworthiness… and with many others. One highlight was dining with Rob along with his Cambodian fiancée’s family, his future brother-in-law chatting away with us vigorously in pigeon English, alternating questions, jokes, laughter, and directives to “eat more frog legs!” faster than we could keep up (the frog legs, fried with lemon grass and chili, were delicious).

Dinner with Rob and his bride-to-be (before other family members showed up).

So what of the dark cloud? What of the Khmer Rouge? As I learned more about the regime I was shocked to discover that the horror was—if anything—worse than I had previously imagined. In the four years that “Red Khmer” controlled Cambodia, over two million people died from starvation, torture, and brutal killings—a full quarter of the country’s population at that time—making the period deadlier on a per capita, per nation basis than the American Civil War or the Rwandan Genocide.

An image painted by one of the few S-21 prison survivors.

Pol Pot’s communist “revolution” was the most radical ever attempted, making the Soviet and Chinese programs look sensitive and gradual by comparison: in 1975 all foreign ambassadors were evicted, schools and hospitals were closed, banking, currency, and private property were abolished, and religion, romance, and family loyalty were outlawed in one fell swoop without any kind of gradation schedule. Cities were turned into ghost towns as residents were driven into the countryside to perform fieldwork, where they were expected to produce incredible rice yields on meager rations (though many of them were lacking the most basic agrarian knowledge). Power was placed in the hands of the “pure” peasants and children, who were taught to obey all orders and use force indiscriminately, while former city dwellers and “educated elite” were considered corrupted beyond redemption, and thus expendable (excepting party leaders like Pol Pot, who were generally the best-educated of all).

One boy who was arrested then tortured and killed at S-21.

This was the high point of the regime. As the city dwellers failed to produce great quantities of rice, everything got worse. Rations were decreased below starvation level while work hours were prolonged, and violence escalated. Pol Pot, unable to believe that his revolution could fail, suspected corruption within the party. Cadres and lieutenants were arrested and sent to Security Prison 21, where they were tortured until they confessed to working for the KGB, CIA, or Vietnamese government. Then they were asked to name fifty more conspirators (who were predictably brought in next) before they were taken to the killing fields. Their wives and children, charged “guilty by blood,” were also killed (the children usually by beating their heads against trees). These killings were mostly carried out by "pure," barely adolescent teenagers. In the countryside the educated were asked to step forward for “forgiveness,” then beaten to death, while everyone everywhere starved. If the Khmer Rouge had not antagonized Vietnam to the point that the Vietnamese army invaded in 1979 to topple the regime, it is likely that the Cambodian population would have been totally exterminated within a matter of two or three more years, Pol Pot left alone in his utopia, atop a monstrous pile of skulls.

Skulls of victims at the Choeung Ek killing fields.

This is what the kind, smiling, laid back people here have been through. Since the deadly regime was toppled things have been infinitely better in the sense that people aren’t dying by the thousands, but in many ways Cambodia is still in the early stages of recovery. It took decades to rid the country of the last Khmer Rouge insurgents (whom the American government supported gainst the Vietnamese into the 1980s, and who were active into the mid-90s), and the country is still littered with millions of land mines laid to keep those insurgents at bay. Despite a UN attempt to promote fair elections in 1993 the current government remains an offshoot of the one installed by the Vietnamese in 1979, rather than the people’s choice, and is largely irresponsible and unresponsive, making little attempt to meet its nation’s basic health and education needs, relying instead on foreign aid (much of which seems to vanish as it enters the country). Corruption is rampant and widespread (with Transparency International ranking the country in the bottom 1% in their worldwide corruption index). Many former Khmer Rouge leaders and cadres are in powerful positions in the current government, and many more live ordinary civilian lives, having never been asked to account for past deeds. In 2006 an international tribunal was established to try the most senior KR leaders, but it has met with numerous bumps in the road, and only one person has been convicted to date, with their sentence now being appealed.

After the bows and the smiles and the gracious hospitality, these realities did come out in my discussions with Cambodians. In hushed tones people asked me if I had visited Choeung Ek, then explained how they were attempting to process the horrors of their country’s past. “How could this happen?” They asked me. “And why?”

As if I could provide any answers.

“This past is not taught in our schools,” said Sa Vorn gravely, before going on to tell me of Cambodia's widespread corruption and how it affected his job, along with other grievances he had with the government. Then he smiled, picked up the English grammar book that he spends all his spare time studying, started up his tuk-tuk, and drove us on to the Bayon… one of Angkor’s largest and most impressive temples, built by Cambodia’s most beloved King at the height of their empire’s splendor. The sun was just rising, and there was not another soul in sight.

Sa Vorn, studying his English while he waits for us at a temple stop—no kidding, that's a grammar book.

And this has been my experience of Cambodia. Learning about one of the worst autogenocides in human history while interacting with some of the nicest, most laid back people I’ve ever met, in the shadow of a staggeringly majestic bygone era. I don't know if Cambodia is like Australia, but it certainly isn't like any place I've ever been.

This, again, is why I travel.

The Bayon at sunrise.

Related slideshows:

Bonus! A few interesting facts about Cambodia:

- Buddhism is the professed faith of 95% of Cambodia's population, which is the highest percentage of Buddhist believers in the world (tied with Thailand). All Cambodian men over the age of sixteen are expected to serve some time as monks as a kind of right of passage.

- Cambodia's chief cultural influence is India, rather than China.

- Unlike neighboring languages like Thai, Lao, and Vietnamese, Khmer is a non-tonal language.

- While Cambodia has its own currency (the Cambodian riel), its use is limited mainly to pocket change, with the country's main legal tender being the US dollar (which all ATMs dispense—at amounts up to $2000 per go!). Generally you pay for things in dollars, and get any change less than $1.00 back in riel.

- Cambodia is the cheapest place in the world to buy certain electronics, notably Apple products, high-end cameras, and other items with relatively determined retail values. Prices are typically equal to their counterparts in the United States (where electronics are still cheaper than most "hyped" locations in Asia due to market differences), but have the advantage of being completely untaxed to everyone.

- Cambodians like their beer with lots of ice. Which of course makes sense for a country with Cambodia's climate.

Another “journey in review,” this time courtesy of my lovely tech-savy wife :).

A few weeks ago I wrote a glowing review of the experiences Marisa and I had while traveling in Taiwan… a jovial celebration of the vulnerability of extended travel, and the wonderful encounters that come out of it. I made a game called “The Kindness of Strangers,” dedicated to all the nice people who helped us along our way. I emerged from Taiwan radiant, optimistic, almost high on the joys of traveling, and the general decency of the human race, excited to continue on and get high all over again in Vietnam.

I suppose I was being naïve. The idea of living life in a perpetual high, whatever brings that high on, is rather ridiculous. Because highs are called “highs” for a reason: if even a small percentage of the population could maintain them indefinitely, they would be called “flats” or simply “life general.” Highs are balanced by lows, and slopes in between. People can’t maintain highs because the world is not of one kind, is not all abundance: a certain drug might make me feel happy, but eventually my supply will run out; I can stuff myself full of food on Thanksgiving Day, but still someone in North Korea will die of starvation; I may encounter ten ridiculously kind strangers in miraculous succession, but turn a corner and I will encounter someone who isn’t so nice. And of course, vice versa. The world is neither white nor black, abundance nor lack, good nor evil, but a mixture of both; in the vocabulary of Asia (and the lens through which Neil Jamieson examines Vietnam’s culture and history in his excellent textbook): yin and yang.

All of this seems ridiculously obvious as I write it, but for me it’s important to remember, because I am prone to extremism, and placing a disproportionate amount of weight in whatever experience I’ve most recently had, or happen to be examining at the moment: this thing that I’m experiencing right now, this is what the world is like. And so my most immediate experience becomes a lens that colors my entire perception of the world, prejudiced greatly over previous experiences I may have had. (Incidentally, I recently finished reading Daniel Gilbert’s rather interesting psychological “detective story,” Stumbling on Happiness, and it appears I’m not alone in this behavior: in general, people seem to be incapable of accurately remembering past experience, and how it made them feel, over the way current experience makes them think that past experience made them feel).

I begin with this perhaps-tedious philosophical drivel, because the encounters Marisa and I have had in Vietnam were by and large so strikingly different from the encounters we had in Taiwan, and I have been trying to make sense of that difference, and also to keep some kind of perspective.

In Taiwan, it seemed that everywhere we went people were simply ridiculously nice to us. So consistently nice to us, that by the time we had been there a couple of weeks we came to expect it, and we let our guards hang low all the time: when the first truck we hailed on the east coast pulled over to hitch us, we didn’t hesitate to throw our bags in the back before we got in ourselves (though we “knew” we should take basic precautions, we just couldn’t bring ourselves to feel cautious at the time, much less suspicious), and when a man in Hualien offered to drive us to the bus station because taxis were rare, we didn’t even think to ask him how much money he wanted (because no one who had helped us had ever wanted any—and he was no exception), never mind thoughts of anything worse.

In Vietnam, by contrast, it seems nearly everyone we’ve met has wanted something of us, and in some cases they’ve been prepared to take it whether the item in question was offered or not. “Friends” have turned out to be mercenaries, and strangers to be swindlers, most of them fairly aggressive. A lot of this “swindling”, mind you, has been unexceptional and—somewhat ironically—simply taken the form of aggressive, unfettered capitalism: guest houses quoting us prices in US Dollars, then insisting on a ludicrous exchange rate if we didn’t settle it ahead of time; taxi drivers setting their meters at the wrong price point because they thought we wouldn’t notice (then getting angry and aggressive when we wanted to disembark); hotel managers selling us $5 bus tickets that actually turned out to be worth 50 cents on packed minibuses full of vomiting children; or, at the start of it all, the government charging us a seemingly arbitrary price for our visas as we entered the country (then shortchanging us when we didn’t have the exact amount they wanted).

On one level, it’s obvious that none of these interactions constitutes “pleasant” by definition; but on another level, it’s hard for me to fully articulate (or defend) why they bother me, when I feel that I should have expected them all. Vietnam is a very poor country, and with ninety million citizens, it ranks thirteenth on the global population scale. The economy, while one of the world’s fastest growing, is still small; per capita GDP sits at a meager $1,100, and prices are low. In this context, next to the average Vietnamese, I am probably not quite a billionaire, but a solid millionaire at least. Why shouldn’t I pay more for a taxi, or a bus ride? Why shouldn’t I give tips out for everything? I’m in a communist country, after all, so why shouldn’t people use their capitalist wile against me for the socialist end of redistributing wealth? Such activity may be inconsistent and unregulated, but it serves the same purpose that a wealth tax does in developed western nations. The idea, in theory, doesn’t bother me.

Nor does the actual monetary loss. Indeed, our net loss in all this swindling amounted to nothing more than a small mound of pocket change (well, maybe a big mound, but still: pocket change). The idea of contributing something to the Vietnamese economy—as someone of relative wealth passing through the country and availing myself of that economy—actually appeals to me. I want to contribute.

What bothers me, I guess, is the way that everything happened: the feeling I was left with after all these encounters. The feeling that I’d been cheated out of money I didn’t even care about by someone I was hoping to have an amicable interaction with. The feeling that people were sometimes taking great pains to hoodwink me, when I would have gladly paid them more had they asked in a nicer way (or at all). But of course, you can’t buy friendship, and anyway I suspect the unfortunate reality behind many of our encounters was the simple fact that most of the people we interacted with needed money more they did friends.

Another fact to take into account is that most of the negative encounters we’ve had in Vietnam have been with people “of the trade”: people in the business of dealing with (and hustling) tourists and travelers on a regular basis. Vietnam has been on the backpacker trail for a long time, and the country is narrow, which makes it difficult to get off the dreaded “beaten path.” There’s still plenty of wonder to be had on that path (I’ll get to that in a minute), but it’s probably not the best place for authentic, endearing encounters with ordinary Vietnamese. In Taiwan we never gave much thought to getting off “the path,” because we never felt like we were on one: the journey felt more like a journey, and less like a scuttle from one carefully prepared tourist trap to the next.

Finally, in the interest of full disclosure as I describe my perceptions, I will say that towards the start of our time here (while we were still in Hanoi, visiting with Marisa’s family), Marisa’s sister’s hotel room was burgled as she slept; and towards the end of our journey, in Ho Chi Minh City, my camera was stolen out of my hand. I relate these incidents only for full disclosure, because I am well aware that my camera being stolen is more reflective of my own silliness (venturing into the chaos of Tet in Saigon with anything of value) than it is of any part of Vietnamese culture or society. There are thieves everywhere, just as there are kind people everywhere, and I know this. But as we travel, we don’t encounter the objective, we don’t encounter what we know, we don’t encounter statistics. We encounter a unique, bizarre, subjective train of events, that color and change us whether we want them to or not, which is my point. I think as travelers it’s important to realize that, important to admit it.

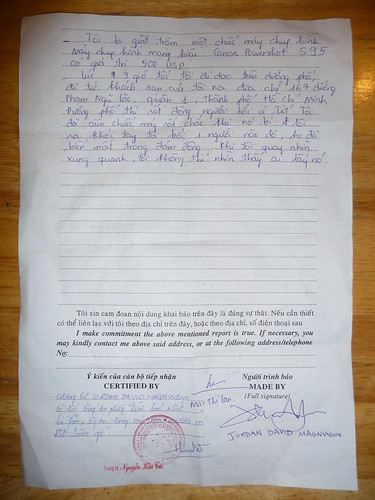

The police report for my camera’s theft… not an easy task to acquire (but necessary for an insurance claim)!

When my camera was stolen out of my hand, in that mass of people, all of whom seemed to be after me (I had physically caught three people going into my pockets before the camera was tugged out of my grip), that moment seemed to me to epitomize my experience in the country. Later, as we waited for a city bus to take us to Saigon’s inter-city terminal, I watched pickpockets hawk their wares to locals, right in front of my eyes (watching hopefully, resentfully for my camera), and I was stunned that no one seemed to care (why should they? A foreign millionaire loses a watch to a poor resident thief… reasonable redistribution, right?). At that moment, that moment seemed to epitomize my experience in the country.

And in some ways it did. But of course in other ways it did not. Despite all these negative encounters I’ve touched on, there were naturally (and happily) moments to balance, moments to bring perspective. Our interactions with people generally did not leave us with the rosy glow that our encounters in Taiwan did, but there were noteworthy exceptions. For example, towards the end of our trip, in the Mekong Delta, a young man we met online offered to take us for lunch with his girlfriend. He was on leave from university in Saigon (for Tet), and was insatiably curious about our travels. We had a wonderful interaction over some delicious street food, and at the end of our meal he presented us with a hand drawn portrait of Marisa and I he had sketched from our photos online (and he didn’t want money for it!).

Later, in Can Tho, another university student offered to host us for two nights in her tiny shack of an apartment where she lived with her sister… her “beautiful apartment” she called it, and it was. She insisted on giving us her bed, and smiled like our intrusion was the best thing that ever happened to her. We went out for smoothies with one of her university friends (who was translating Hawking in his spare time “for fun”), and the discussion we had with them while sipping down delicious fresh fruit was one of the highlights of our entire trip. These bright, friendly, optimistic individuals were an amazing contrast to the people who’d recently been ripping us off, and talking with them (about everything from anthropology to astrophysics to politics to American Idol to Facebook and censorship) helped bring needed perspective to our journey.

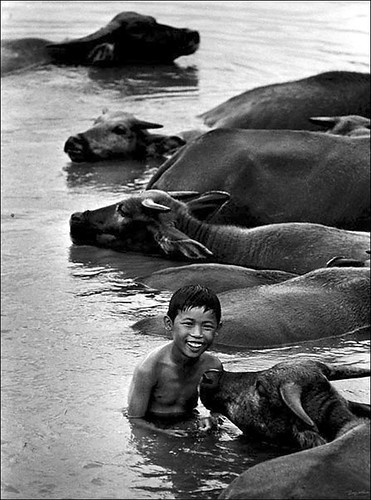

Or there was our encounter with Long Thanh: Vietnam’s most celebrated photographer. While in Nha Trang we went looking for his studio, as Marisa and I are both rather keen on photography; we were especially curious to see some of Mr. Long’s more famous works that we’d heard about, like his photo of a rural Vietnamese boy running across the backs of several submerged water buffalo, which (like many of his pictures) has won him a number of international awards. When we arrived, the studio seemed to be closed (it was Tet-eve, after all), but when we knocked, a young woman opened the door. We took our shoes off and went inside, appreciative of the cool air and quiet surroundings. The space consisted of three consecutive wooden-paneled rooms, lined top-to-bottom with black and white photographs. Long Thanh has been in the business of picture taking for over fifty years, but he has only ever had one subject: Vietnam, and he has only ever envisioned her in black and white. The large print photos were stunning.

Photo copyright Long Thanh.

Still, the real joy of the visit came later on when an older man entered the studio, and began talking with the young woman we had already met, as she showed him something on the hefty digital camera she held in her hands. After a moment, the man took the camera and held it up for us to see a photo of two sleeping cyclo drivers on its rear display: “my daughter took this picture just this afternoon,” he beamed. To make a long story short, the man turned out to be Long Thanh himself, and the woman his daughter. They wanted to keep the gallery open over Tet, so Long’s family was coming to him (his home, he explained, was just upstairs from where we stood). Over the next twenty minutes Mr. Long offered us interesting anecdotes about several of his photos, and before we left we made sure to ask for his best advice for budding amateurs like ourselves; his answer was hardly surprising: he told us to keep our eyes open.

Or there were the chats Marisa and I had over breakfast with a Vietnam War veteran who was staying at our hotel in Saigon; a Michigander who had fathered two Amerasian girls during the war. He told us how he had come back twenty years after the fighting to find them; how he had been wrenched with guilt when he discovered that the older of the two had been murdered, but how he found the other and was reunited happily with her. Now he has a house in Dalat, and was only in Saigon to settle some paperwork before being married to his Vietnamese fiancé.

Besides these happy interactions, there were Vietnam’s natural and historic wonders to inspire us, and those moments of being in a place and feeling amazed to be there, to be traveling, to be alive:

Flying through the countryside in the early morning in Ninh Binh on the back of a moped, watching rice farm after rice farm wiz by, then bam: a giant vertical karst emerging from the center of one of those rice fields. Then another. And another.

Whipping around one of those rocky monoliths and catching site of mammoth Bai Dinh Temple, in the process of being built… soon to be the largest Budhist complex in Vietnam.

Walking around Hue’s Citadel in the light morning rain, no one else there; the flowers and the moss on fire from the rain, burning green instead of yellow or orange; tiles glistening and shimmering; old moats threatening to overflow… a perfect morning to get lost in a fascinating old structure that’s been to hell and back.

Days on the train, feeling connected to generations of travelers who have gone before, who have sat and looked out the window and listened to the clak-a-ty-clak of iron horse wheels as one place turns into another.

Related slideshow: Vietnam Top 10 Train and Bus Shots

Taking the night bus from Hue to Nha Trang. A miserable experience, but an experience nonetheless. Travel doesn’t feel right to me unless there’s some discomfort involved at least some of the time.

Arriving tired and sore in Nha Trang at 5:00am, but feeling joyful as I watched the sun rise over the beach as locals exercised, before catching a few more zzz’s and diving into the five-foot waves.

Finally, I can say that some of the swindling we were subjected to actually lead to a few of our most memorable and interesting experiences. For example, I complained about being sold $5 “tourist bus” tickets for 50 cent “anything but” bus rides earlier, but again, my main grievance was with the way such transactions happened; taking packed local transportation, while not the height of comfort, is an experience I’m happy to have, and the local Vietnamese minibuses are amazing in the way they operate: they have advertised destinations, but will take anyone any part of the way between their two endpoints. People don’t wait for the bus: rather, each one has a worker who hangs out the door, calling out to everyone who passes, and metaphorically and literally pulls people into the fun (and not just people, but goods as well: one bus we were on picked up a large delivery of strong-smelling mushrooms). The main rule of thumb on these busses is that there is no such thing as “too full.” I wasn’t lying about the vomiting children either: one young tyke very narrowly missed a headshot opportunity that would have made the experience even more memorable than it already was.

And this, probably, is as good a place to end as any. Vietnam has offered us mixed experiences, but even those experiences that weren’t particularly comfortable or fun have still been experiences. Travel isn’t about the good things, or the bad things: it’s about all the things that happen to you while you’re in another place. It’s about trying to make sense of what you can, but ultimately, I think, about simply accepting the sum total, which will inevitably be more than can be analyzed or synthesized (and analysis and synthesis, valuable as they are, are not equal to and cannot replace the raw experience itself).

I started this post by reflecting on the negative interactions we’ve had here, not because I feel a lasting dislike for Vietnam, and want to vent some kind of revenge, nor because I think such interactions represent this country in any kind of holistic or objective way. Rather, I started the post the way I did because I am writing about the subjective experience of travel, and as we leave Vietnam the difference between the way we were treated on average here, to the way we were treated in Taiwan—and the effect that difference had on us—is too striking a part of our personal journey to overlook.

It is not about “Taiwan vs. Vietnam,” but about our particular experience in visiting Taiwan, and then Vietnam: because it’s impossible to travel without context, without a “before,” and an “after.” It’s about the fact that I left Taiwan rosy and optimistic, carefree and trusting, and that—despite the good times I’ve recounted—I am leaving Vietnam feeling somewhat cautious, suspicious, and cynical, with an eye to protect what is mine. This change in me is what I think about as I leave this place, and I ask myself, why? Why was our experience so different here? Was it the poverty? Was it the tourist trade? Was it our lack of effort in getting off the beaten path? Was it our unreasonable optimism and naivety brought on by the ridiculously positive experience we had in Taiwan? Was it the distorting lens of significant negative events, like having my camera stolen? Were we just unlucky? Was it all in our heads?

I suspect a bit of all of the above. Whatever the answer, our experience is what it is, and I don’t regret it. Sometimes travel makes me feel like I’m living on a cloud, sometimes it brings me back down to earth. Such is life. Such is the world. And that’s what I’m traveling to encounter. Whether inevitable or not, our experience in Vietnam was in many ways simply a balance to our experience in Taiwan, and I believe that balance is almost always good: yin and yang. What will Cambodia be like?

Related slideshows:

Related resources:

The last few weeks have been, for me, mostly a vacation. In early December Marisa and I left Taiwan after forty days of trekking there, and flew to Hanoi, where Marisa's parents—who have been teaching overseas around the world for many years—are helping to start an international school. Marisa's sister joined us when her university let out partway through December, and we had a great time celebrating the holidays together. The Sauters generously put us up in their apartment, and insisted on feeding us for the duration of our stay. So for the better part of two months Marisa and I left behind the day-to-day uncertainty of our extended journey for a comfortable and enjoyable homestay with family. I say that the time was mostly a vacation to contrast it with the purpose and quality of our journey as a whole: to clarify that Game Trekking, for me, is not a vacation.

Having fun in Hanoi with Marisa's sister and parents, Kumquat trees in the background.

I take the time to clarify this issue, because some people have admitted to being baffled as to why anyone would fund me for what they perceive to be an extended "time off," and others have outright accused me of using Kickstarter to fuel a long-term holiday. I don't take offense at these questions or accusations, as I think the confusion is understandable: people often travel when they go on holiday, and for many others, it is the only time they travel. But that does not mean that travel and vacation are inextricably linked—they are, in fact, quite distinct concepts.

A vacation is about taking time "off," time "out." It is about taking time to rest and renew. People do this in a variety of ways, but in connection with travel it typically means lying on a beach somewhere and sipping a lemonade as the sun sets and you let your mind wander. In this sense—perhaps the most important sense—vacation is a mindset. One cannot be on vacation if one does not seek to be on vacation… one cannot be on vacation if one is actively pursuing goals other than rest and relaxation… one cannot be on vacation if one is spending energy, rather than saving it.

The Game Trekking project is not about saving energy, not about relaxing: for me, the project is about pushing myself, challenging myself, setting high goals and attempting to meet them… it is a journey of the mind, a journey of the senses, a journey of the (dare I say) heart, with multiple dimensions. I seek to learn something about the world by coming into contact with new places and different cultures in as "real" and "raw" a way as I can, always choosing adventure and meaning, connection and challenge over ease and comfort; when I find myself wanting to choose what I find comfortable over what might be meaningful (which happens quite often), I try and check myself, and go back the other way (I don't mean to imply that I am in any way peculiarly heroic or brave: "going back" might mean something as simple as talking to that stranger on the corner, rather than walking past). In pushing myself this way, I seek to learn not only about the world, but also about who I am. Beyond that learning, I seek to convey something of what I discover to others, via this blog, via my photos, my videos, and my reading lists. And finally, I seek to do my best to stretch a new and exciting medium (computer games) and use it in ways that it hasn't been used before. Game Trekking for me is the opposite of vacation, is the opposite of checking out or taking time off: it is about checking in in the most vital ways I can think of, about those things in life I believe to be most important: searching, striving, giving, receiving, dialoguing, and attempting to create. From the small things (not being able to carry enough eczema cream to stop the chronic itching) to the big ones (attempting to keep my long-time struggle with depression at bay while maintaining my enthusiasm for game development in the face of perpetual movement) this project manages to challenge me every day of the week. And that's what I want it to do.

Of course, that doesn't mean you should fund me. Some may (and do) see my goals as entirely personal, and irrelevant to them, regardless of how much I'm pushing myself and trying to live rightly (which some may see as pretension). And that's okay with me. I would not for a minute pretend that this project is an objectively vital one that everyone should contribute to (if such a project could exist): rather, it is a project that some may latch onto because it resonates with them in some way, because its goals are goals they share. I don't intend these paragraphs to be a defense of Game Trekking, but rather a simple explanation of how the project differs from vacation time, for those who are genuinely curious.

But to get back to the point that got this tangent started: Hanoi for me was mostly vacation. It was a time to relax and renew, enjoy the holidays, celebrate being with family; it was mostly time off from my trek. I say "mostly," rather than "totally," because it was still a great opportunity to live for some weeks in a fascinating foreign city, and experience something of life in Vietnam. Marisa's father lent me his bike, and one highlight for me was simply biking around West Lake day after day…

…past every manner of thing on mopeds:

…and bicycles:

…past fishermen:

…and men about to be married:

…past Vietnam's beautiful and eclectic architecture:

…churches (as I read of Christian persecution in the country):

…and temples (Buddhists and Taoists have faced persecution too):

…past sweethearts on mopeds (you can park anything on wheels):

…and Ho Chi Minh's body, in its grand mausoleum (he goes to Russia once a year for "maintenance"):

…once I stopped to get a haircut:

…and once to fix the electric wires (just kidding, that's not me):

Other highlights included a trip to Hoian, a city that used to be a large multinational port, and features a fascinating mix of artifacts from the French, Chinese, and Japanese… like this old Japanese bridge:

…and a boat ride to Perfume Pagoda:

All in all it was a great few weeks, and despite being in "vacation mode" I managed to continue my reading, and start in on a couple of game ideas that I hope to share with you soon (moped balancing act, any one?). Marisa and I left Hanoi on the twenty-fifth of January, and have been heading South since then, mostly by train. I hope to share those adventures with you soon! If one aspect of vacation is knowing where you're going to be sleeping more than two nights in advance, then I can safely say that we've transitioned back out :) .

Related Slide Shows:

After more than a month spent trekking through Taiwan, after 200 miles of walking, 4000 photos, 7 blog posts, many hours at my laptop, and one monkey in my lap… the first games of the Game Trekking project are finished and available to play. I hope they are not the best games I will make for this project, but they are my best attempts so far.

One of my chief reasons for embarking on Game Trekking was the element of challenge; in that regard, the project hasn't disappointed. One of the main challenges has been attempting to sustain and nurture my enthusiasm for extended travel—for facing the unknown day after day, for the perpetual lack of routine, for the permanent homelessness—while also sustaining and nurturing the energy and capacity for creative output. I've been slower in that creative output than I would have liked, and have less to show after more time than would be my preference. But I am learning to balance these dual aspects of my new life, and am optimistic for the future.

Another great challenge has been deciding what to make my games about. While I cannot see everything there is to see of Taiwan, or Vietnam, or any other country, on my travels, it is a hundred times more evident that I cannot make games about everything there is to make games about. I can see a hundred or a thousand things, while I can make games about one thing, or two. Then there is my reading, which provides me with a vital balance to my experience in understanding the places that I visit, and also provides me with a thousand more game ideas. Should I make a game about Taiwanese pirates in the sixteenth century, or about that monkey that jumped in my lap in Kaohsiung? Should I make a game about Taiwan's political struggle with China, or about the many kind people who helped us while trekking?

I can do nothing but latch onto those things that jump out at me specially, those things that press themselves upon me, those things that make me especially happy, or especially sad, those things that seem especially important… or those things that suggest to me an interesting mechanic for play. Predictably then, the games I make may be more about me than they are about the places that I visit… more about my subjective position in the world, and my response to my own travels, than they are about the world as it exists, or travel as a universal concept. In seeking to make something for others, I can do nothing but make something for myself… and hope that it might be helpful or relevant to others in some way. But I think this is the same "dilemma" that all travel writers face, and more broadly, all creators.

I have decided not to limit myself to making "purely abstract" games or "purely concrete" games, "purely academic" or "purely experienced-based" games, because the two domains for me are too overlapping: I read because I travel, and I travel to provide context for my reading; political realities may be abstract, but they are also concrete in the lives of the people I talk to; knowledge of a place changes the way one experiences that place, while experiencing a place enriches and changes one's knowledge of it.

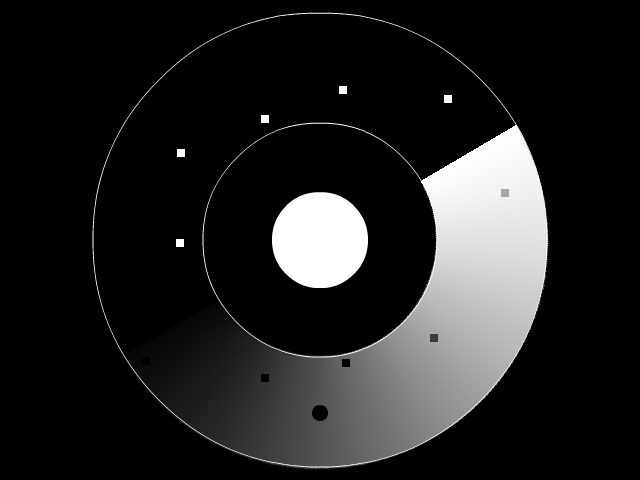

So my first game about Taiwan is an abstract game, a political game in circles and squares, about Taiwan's struggle with China. Because that reality was everywhere I went in Taiwan, and has been omnipresent there for fifty years. Because everyone I talked to, and everything I read kept coming back to it. When I searched for one idea to represent the country, that is the idea that came to me. Taiwan's struggle with China may be cliché as a fact about the country, but that does not mean it is an unimportant fact… I've talked to too many people who thought Taiwan was part of China, to let me think that.

Taiwan screenshot:

You can play Taiwan in your web browser at:

http://www.gametrekking.com/the-games/taiwan/taiwan/play-now

(Note that it changes a bit at 1 minute 50, if you can last that long).

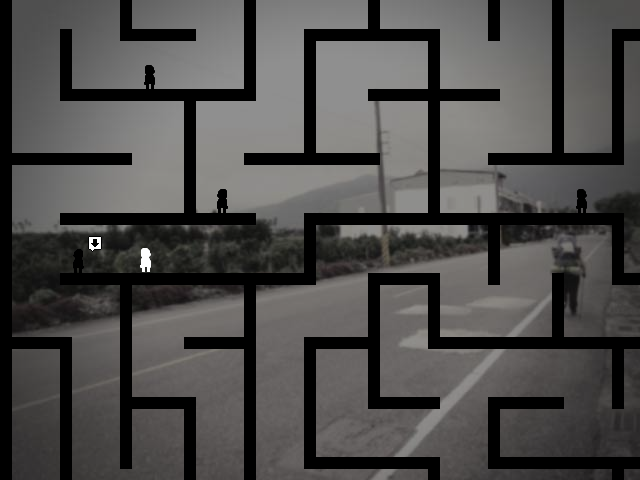

Some people will ask if I needed to travel to Taiwan at all to make such an abstract game, and the answer is yes: the game would not exist without the travel that led, even if implicitly, to its creation. But still, I very much wanted to make a game that captured something of the texture of my day-to-day trekking experience while there, and that desire led to the creation of a second game: The Kindness of Strangers.

The Kindness of Strangers screenshot:

You can play The Kindness of Strangers in your web browser at:

http://www.gametrekking.com/the-games/taiwan/the-kindness-of-strangers/play-now

(Play it a second time to have a different experience).

While I consider these games essentially finished at this point, I welcome any comments or suggestions, and am open to changes in response to feedback. I would especially appreciate knowing about bugs or problems with the games, so that I can promptly fix them.

Special thanks to all of my Game Trekking backers who have made these games possible, as well everyone who provided valuable feedback while the games were in development.

More games about more places are on their way!

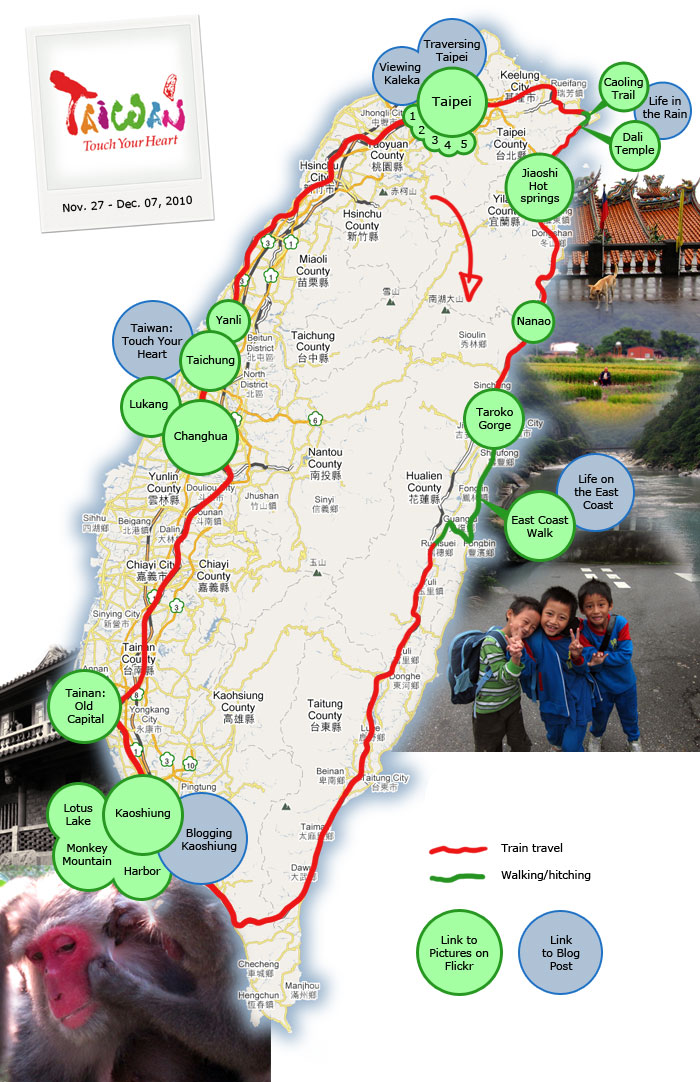

A little interactive map of our Taiwan journey. Click on green circles to go to the corresponding photo album on flickr; blue circles will take you to their corresponding blog post.

If you find this interactive visualization interesting or helpful, please leave a comment, so that I can better decide whether or not to make similar maps for future countries—thanks!

I will remember many things about Taiwan.

I will remember being wet, a feeling that characterized much of the first half of our trip. Walking around Taipei in raincoats every day for a week. Waking up at Fulong Beach to the sound of rain on canvas, enjoying the sound, then slowly coming to realize that the reason my head was cool was because our tent's waterproofing had failed under the relentless downpour. Waiting for the rain to stop, only to have it start again as we hiked through the jungle; making covers for our packs out of garbage bags. Being happy to finally make it to a Buddhist temple where we could spend the night and take refuge under a solid roof.

I will remember Taiwan's beautiful and remote east coast. Hiking the historic Caoling Trail and not minding the rain, because the climb made us hot, and because our surroundings were gorgeous… being surprised at the drastic change in vegetation as we gained altitude. Seeing a truly giant spider outside a small trail-side shrine, dedicated to one of Taiwan's host of Taoist deities. Spending the night on the beach at a small lighthouse village; waking up to the sight of seaside cliffs, and our first sunny day. Hitching a ride later that day in the back of a pickup and thinking there was nothing better than the breeze in my hair, the sun on my face, and the ocean view beside me. Watching monkeys leap through the trees at Taroko, and being surprised that the famous gorge actually managed to live up to its hyped reputation.

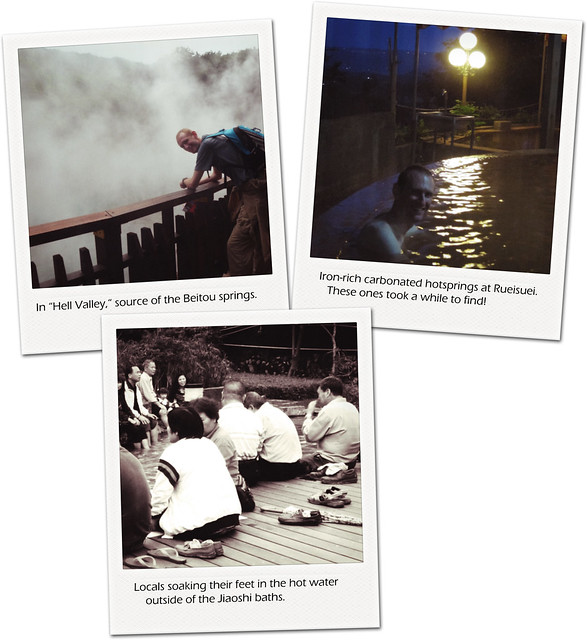

I will remember the hot springs. The feeling of hiking around Taipei for days on end, then finally letting my body drop into the hot water of Beitou, an outdoor bath where we watched the sun set along with locals who went there every day. Sitting in the splendid wooden baths at Jiaoshi that exuded feng shui; baths which a Taiwanese man informed me were so nice "because the Japanese built them." Getting off the train at Rueisuei and walking for miles through farmland in an attempt to track down Taiwan's only naturally carbonated springs; thinking we were lost, then finally making it to the Rueisuei Hot Spring Hotel, where we were the only guests of an eclectic Taiwanese family that loves Harley Davidson. Showering in iron-rich spring water that turned our hair orange.

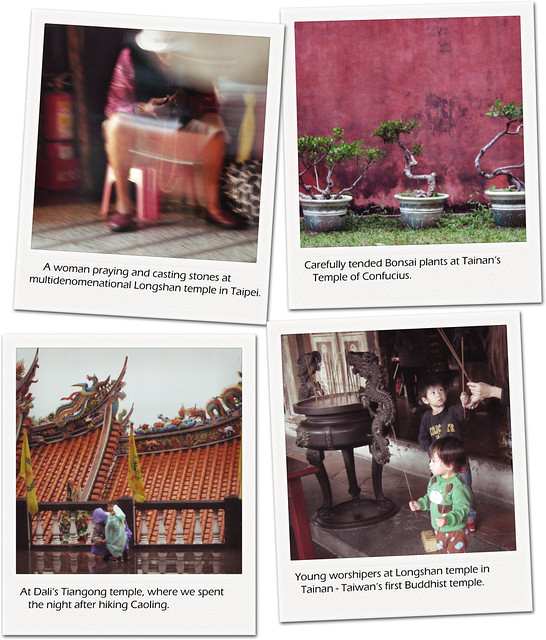

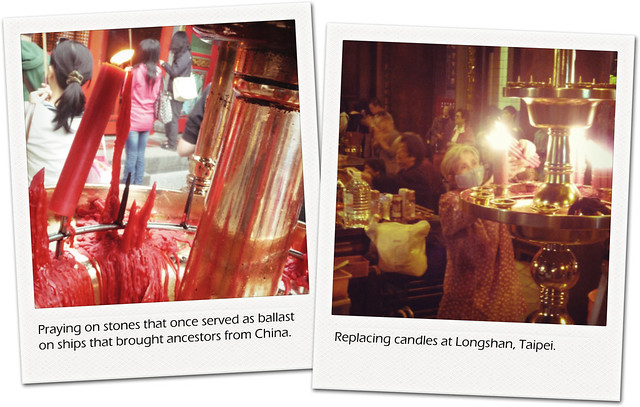

I will remember Taiwan's myriad temples and shrines, Taoist, Buddhist, and Confucian; the Taoist temples overflowing with color and ornamentation, gaudy yet earnest… their Confucian counterparts stark and simple by contrast, manifesting the teachings of old Master Kong. Everywhere we went, no matter how remote, or how busy, somewhere close by incense was burning, somewhere close by someone was bowing in prayer. On the hiking trail, next to a tree: there was a shrine; in Taroko under a bridge: there was a deity waiting; across from a farmer working the fields in Hualien county: there was Matsu, face black from decades of incense.

The temples are tactile places: rough wood pillars sprout up from rough stone floors, large iron pots for incense are cool to the touch, giant wax candles are smooth and shiny to look at; smoke rises in puffs, chants float on the wind, and inside a doorway, through the haze of the incense, you can make out the shapes of fruits and candies which gods like to eat. To your right a woman cleans cubic feet of wax from cubic feet of candles; to your left, a man gives incense to his three year old daughter and tries in vain to guide her in its use. And that is why I love the temples: they are so old, so alive, and there's so much going on; they are places where sitting and waiting, watching and listening, waiting and touching are greatly rewarded—there's nothing quite like running your hand across a stone that ten thousand people have stood on to pray, that served as ballast on a ship bringing immigrants from China 300 years ago, in a country that's made up of ethnic Chinese who don't consider themselves part of the Mainland.

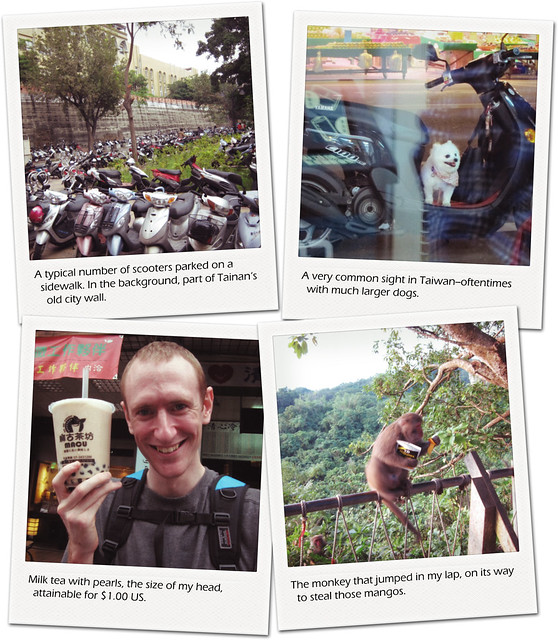

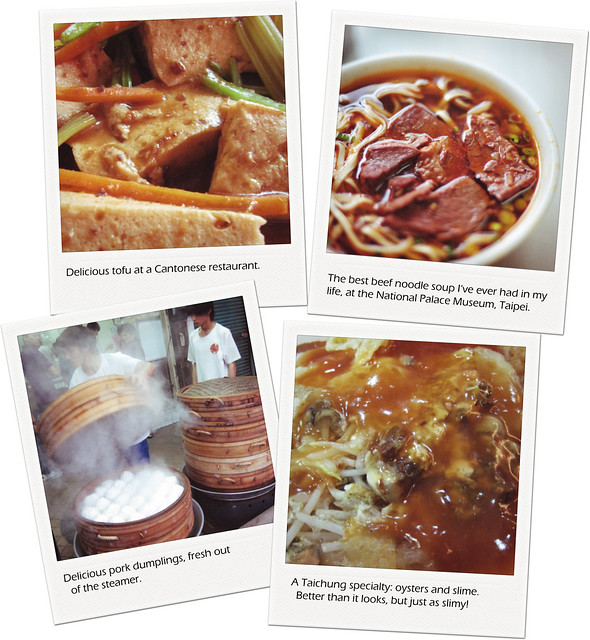

I will remember so many "little" things (if one is heartless enough to give memories sizes): more scooters than I've ever seen before, more dogs per capita than I've ever seen before, more dogs on scooters per capita than I've ever seen before. More bubble tea, cheaper bubble tea, better bubble tea, and more kinds of bubble tea than I have ever drunk before. More monkeys jumping in my lap than have ever been in my lap before. More stinky tofu than I've ever smelled before. More helpings of chicken feet than I've ever eaten before, and also of New Zealand oatmeal (oatmeal making a cheap breakfast, being very popular in Taiwan, and much of it imported from New Zealand).

I will remember the food.

And I could go on. But of all the memories, the ones that I will recall most fondly are of all the times that people helped us; all the times that strangers were kind to us without reason. In Taipei, getting lost, and a woman offering to help us as soon as my map was halfway out of my pocket. In Nanao, a man giving us directions to the local hot springs, then coming after us half an hour later on his scooter, because he had remembered that the springs were closed for construction. Later, going down the wrong remote road on the way to a train station, and having a mother and daughter stop and offer to drive us wherever we needed to go; offer to take us to an alternate hot spring, to an alternate town, to an alternate train station (because the one we were headed to wouldn't take us Town X); offer to host us in their aboriginal village. In Hualien, stopping for dinner at a street-side restaurant where no-one spoke English, only to have a passerby stop his scooter to have a conversation and help us out (a Los Angeleno who was back in Taiwan for military service); turned out to be a Buddhist restaurant with excellent vegetarian cuisine.

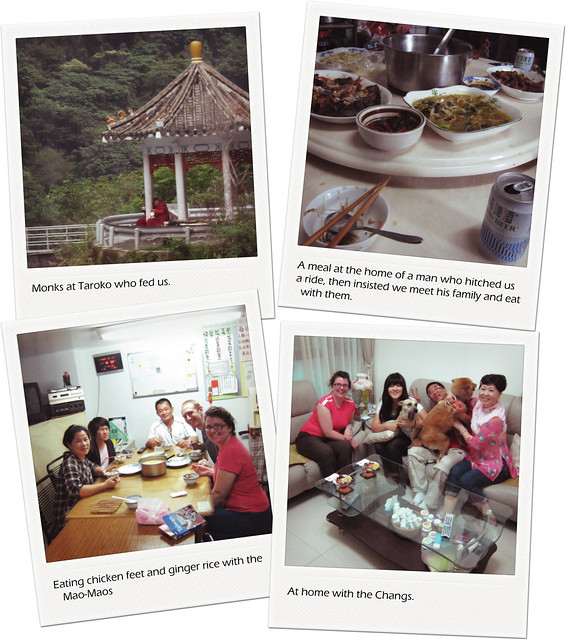

The next day, waiting for a taxi to the train station, a passerby introducing himself, asking where we needed to go, and informing us that taxis were rare, but he'd be happy to drive us to the station (or the next town, if we wanted—they have a great beach there, he said). In Taroko, monks under a pagoda insisting on sharing their lunch with us, delicious honey-bread dessert included… they were returning to their monastery after visiting a friend, and had plenty, they said. Never having to wait for more than one or two vehicles to pass before getting picked up for a hitched ride. Having one older man who hitched us and spoke little English take us back to his home and his family, where he insisted on serving us lunch; "so young," he said, when we told him our age… how I wished I could ask him what he had been doing at twenty-five—what his dreams had been, what he laughed at, what he thought of how life had turned out… but all I could do was touch my beer can to his, and drink.

Then there were the Mao-Maos and the Changs, Taiwanese families who hosted us for three nights in Tainan and Taichung, respectively, and treated us like long-lost family members—despite knowing nothing about us except what I'd posted on CouchSurfing.org. For our arrival the Mao-Maos prepared a special meal of chicken-feet and ginger rice, and in the morning Mrs. Mao-Mao wouldn't let us leave the house until we had been properly filled with rice balls and milk tea. On our second night with them, Mr. Mao-Mao insisted on taking us to an area of Tainan which we hadn't managed to get to, treating us to "special food," and attempting to show us his favorite sights (despite the fact that it was unfortunately late on a weeknight, and most places were sadly closed). Two days later we stayed with the Changs, and despite having only twenty-four hours with them, they managed to take us to more than half a dozen locations in Taichung and Yanli and stuff us to overflowing with delicious Cantonese and Hakka foods and deserts—absolutely refusing to let us pay for anything, they went so far as to give us presents for Marisa's parents (whom we were soon to meet in Vietnam), and when we left wouldn't let us get on the train without a packed dinner—and hugs all around.

As our train chugged towards Taipei and I ate of my packed dinner bounty, my mind wouldn't stop spinning: who were these strangers, and why were they so kind to us? Who were these people who took us, sight unseen, into their homes, and treated us like family—who let us sleep next to their laptop computers and digital SLRs, and lavished food and gifts on us? As our train pulled into Taipei Station—a place that felt strangely like home, because we spent our first days in Taiwan there—I had no real answer. As I sit here at my parents-in-law's home, having just arrived in Vietnam, I still have no real answer. But what answer am I looking for? Part of me seems to believe that these kind folk we visited must have secret identities: that they are the Batmen and the X-Men of doing good—kind people who have planted themselves in wait for us, to achieve some special purpose. But I know that is not true—I have had too many encounters with too many kind people in too many countries, and I don't believe in Batman. No, these people are just ordinary people, and that reality is a large part of why I travel: because for every terrible story my grandmothers have related to me from newspapers or television, of physical violence, or kidnapping, or theft… for every one of those, there are two, or three, or four stories of someone in the world who's been unreasonably kind to a stranger… and it gives me hope to be part of those stories—now on the receiving side, but I hope, throughout my life, to be on the giving side as well.

"Kindness begets kindness, trust begets trust, hope begets hope"; It's one thing to see that as a nice, clichéd sentiment, but another thing entirely to experience the reality personally in a way that I can't deny. Have I experienced kindness from strangers before? Have I offered it to them? Certainly. But one forgets, I forget. Not that it happened, but the way it felt, the way it changed me… and so the sentiment becomes a sentiment once again, becomes cliché once again, and I distance myself from the most important things in life. The vulnerability of extended travel, and the encounters that come out of it, force me back to the center.

Taiwan's official tourism motto is ridiculous, but after our experience there I can't help but like it, can't help but feel that it's exactly what it should be.

For the last couple of weeks Marisa and I have been staying with my friend Simon Braunstein in Kaohsiung, Taiwan's second largest city, located on its southern coast. After trekking around continuously for two weeks, rarely spending the night in the same place twice, Kaohsiung has served as a kind of stable island, where I've been able to put together the shells of two small computer games. Of course, we've also taken the time to get out a bit, and see some of Kaohsiung's sites. Highlights include:

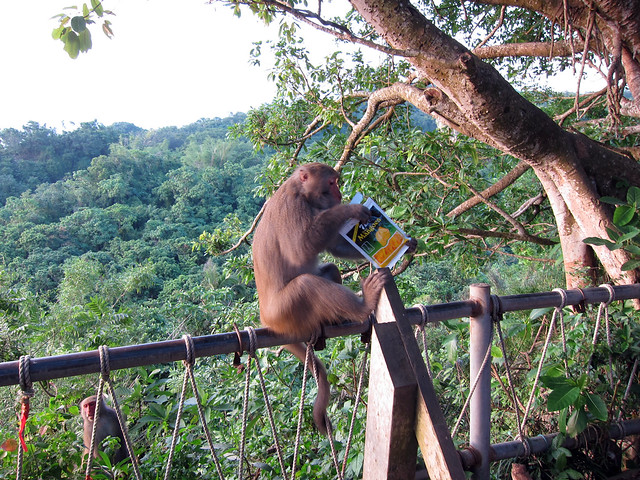

A visit to Monkey Mountain, right in the middle of Kaohsiung, along the coast, which, true to its name, is home to many, many monkeys… many of whom have grown accustomed to using the stairs built for hikers, and some of whom have grown accustomed to stealing food from visitors and eating it themselves. The monkey in the photo below actually jumped on my lap on his way to steal Simon's mangoes, which he proceeded to flaunt, and then devour in mouthfuls as other, larger monkeys drew closer:

A long walk around Lotus Lake (or "Lotus Pond," depending, I guess, on how large you require a lake to be—the university I attended insisted on calling the puddle of water to the west of campus a "lake", so I won't insult Lotus' 3-mile circumference), home to myriad pagodas and temples, some of the former requiring that you walk in the mouth of a dragon to enter (and leave via a tiger's backside):

…and some of the later in the shape of the gods they celebrate:

An afternoon spent enjoying the view from the 150-year-old former British consulate at Dagou (which sits on a hill overlooking Kaohsiung's substantial harbor—4th or 5th largest in the world), while having proper British tea (as in the small meal) complete with Taiwan's addition of tapioca pearls:

…I do love old colonial architecture:

Walking most of the length of the nicely decorated Love River, and also taking a ride on a boat (yes, a Love Boat):

And of course, hanging out with Simon and Tina, who helped us properly enjoy the city. In terms of the games… well, hopefully you'll hear about those soon :).

After a week of exploring Taipei, and another week spent trekking down Taiwan's east coast, Marisa and I are now holed up in Taiwan's 2nd largest city of Kaohsiung, where I'm working with my friend Simon (who's generously hosting us) to make a super cool game about rice farming! I'll be posting an overview of our trip down the east coast shortly, but for now, here's a look at one day in the process (Nov. 11), complete with trekking, hitching, lunch with our ride providers, hot springs, and beautiful views.

We started the day at our beach-side campsite on Highway 11:

From there, we walked a little bit, enjoying the clear skies (it was our first truly sunny day in Taiwan), then hitched a ride further down the coast in the back of a pickup:

We had a snack in the small town of Fongbin, walked a bit more, then hitched another ride inland a little ways, to Taiwan's Guangfu, in Taiwan's East Rift Valley (once again, try to ignore my eczema, which makes my face look gross):

The man who took us to Guangfu was kind enough to invite us in for a home-cooked meal with his family, in their house which also served as a store-front for every kind of hardware supply (and a talking bird):

At Guangfu we caught the train further down the Rift Valley…

… in search of Taiwan's only naturally carbonated hot springs, in the town of Rueisuei. The hot springs weren't quite as easy to find as we expected, but after walking several miles through farmland, and asking numerous people for directions, we finally got there!

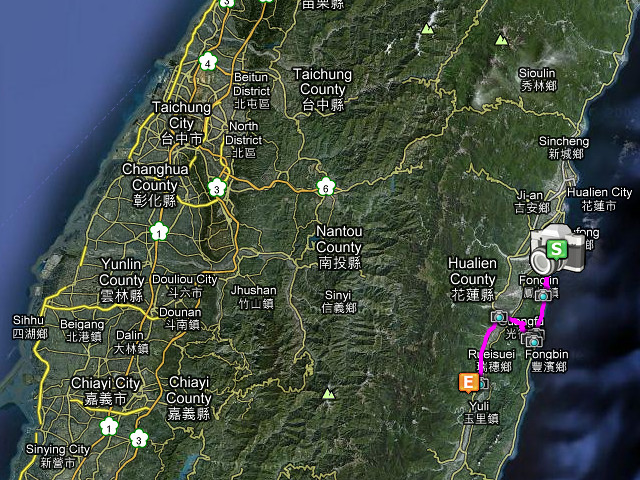

Here's a little map of the ground we covered that day (click on it to get an interactive view, with pictures):

You can also check out more photos on Flickr.